Deep Reads Part Two: The ability and the will-power, Neville Bonner 1971-1980

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware this blog post contains images and references to deceased persons.

Continuing the story of Neville Bonner’s remarkable life, we explore how his relationship with Heather Ryan intensified his interest in politics and led to a major career change in the 1970s.

In 1971, while Neville Bonner was still employed as a bridge carpenter, the Liberal party invited him to fill a Senate vacancy created by the early retirement of Dame Annabel Rankin. He was appointed in the Queensland Parliament on the corner of George and Alice Streets on 11 June. The Women’s Weekly ran an article about it, aptly titled ‘Warm-hearted Mr Bonner makes history’. On 17 August 1971 he was sworn in at (Old) Parliament House, Canberra. In an almost overwhelmingly emotional moment, he felt strongly the presence of his Aboriginal ancestors and that ‘the whole race was on my shoulders’. It was a feeling that would remain with him.

Neville and Heather Ryan were to marry in 1972 on the lawns of the One People of Australia League (OPAL) offices in Eight Mile Plains, and to remain together for the rest of their lives. They lived at 3 Short Street, Ipswich, where Neville maintained an office, and are buried together in the Warrill Park Lawn Cemetery, Willowbank, under the epitaph ‘Thy will be done.’

Neville was to be publicly elected as a Queensland Senator in the four elections between 1972 and 1980. Reflecting on his career, he stated;

‘My first responsibility was to God, because I’m a Christian; my second responsibility was to my nation, because I’m an Australian; my third responsibility was to my state, because I’m a Queenslander; my fourth responsibility was to the party that I was a part of and who gave me the opportunity to get into Parliament.

But interwoven through the whole sequence was my almost all-consuming, burning desire to help my own people, the Aboriginal community, to become respected, responsible citizens within the broader Australian community, retaining, where desired, ethnic and cultural identity but having all of the opportunities that every Australian – other Australian – white Australian – takes for granted: education, employment, health, housing and social and economic standing within the community.’

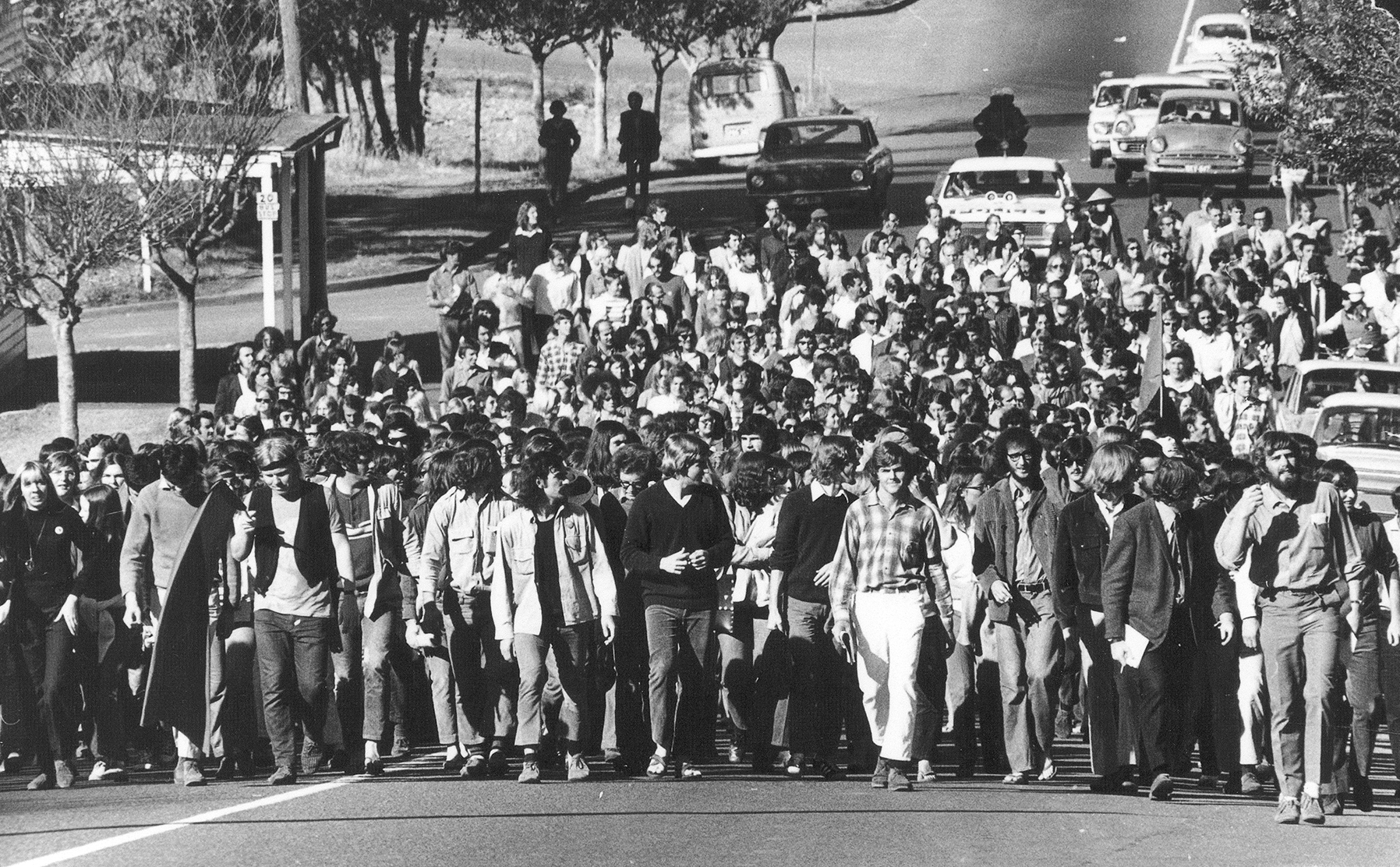

It was a difficult combination of obligations,(5) and Neville was immediately placed in a position where his personal feelings must have conflicted with his public conduct. In July 1971, within weeks of his becoming a senator, the all-white South African rugby side, the Springboks, toured Australia. Impassioned anti-apartheid demonstrations took place everywhere they played. In Brisbane, hard on the heels of the third anti-Vietnam moratorium march that had taken place in the city at the end of June, then Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen declared a state of emergency. This conferred extra powers on the city’s police in the leadup to the Brisbane clash on 31 July – to be played not at the usual Ballymore Oval, but the brick-walled Exhibition Grounds.

Protesters gathered outside the South African team’s accommodation at the Tower Mill Hotel in Wickham Street. Police forced the demonstrators down a slope and ‘many young university students copped a hiding.’(6) (One of them was future Queensland Premier, Peter Beattie.)

The Liberal government of William McMahon supported the tour. Neville could scarcely oppose it within weeks of his appointment. Soon after he left politics, however, he spoke of his detestation of apartheid and his personal experience of such a system in what he called the ‘penal settlement’ of Palm Island in the 1950s.(7)

NITV reported in 2021 that Neville said he knew he would be scrutinised for ‘the way I walked, the way I talked, the way I ate, the way I drank, everything . . . Everything I did was being judged, and the whole race was being judged on it . . . I felt I had a responsibility to prove that we Aboriginal people had the ability and the willpower to be able to handle any situation.’(8)

Between 1968 and 1971, as Neville was stepping up from a branch political membership level to the Federal level, a new group of Aboriginal activists emerged in Australia, advocating uncooperative strategies adapted from those of the American Black Power and Black Panther movements and informed by their readings of Malcolm X, Franz Fanon and others. It was to these people Nugget Coombs referred in early 1973, when he spoke of ‘the emergence of what might be called an Aboriginal intelligentsia . . . in Redfern and other urban centres’.(9)

Brisbane-based Noonuccal man Denis Walker, the charismatic leader of the Australian Black Panther chapter, was one of those who scorned the patient approach of well-known ‘older’ Australian Aboriginal leaders in favour of radical action.(10) In an article in the Bulletin in early 1972 Walker (later called Bejam Kunmunara Jarlow Nunukel Kabool) predicted that it was going to be a ‘far more militant’ year. ‘One thing that people haven’t done so far is challenge the laws . . . everything at every level of the system,’ he said. Neville, by contrast, was reported to have said ‘Unfortunately there are people who are impatient – who lean toward a more radical and violent policy . . . The Queensland Government is doing everything in its power to help the Aborigines . . . Of course there’s still plenty of room for improvement. I’m trying to do a lot in my own way through the right channels, through my parliamentary colleagues.’(1 1 and 12)

Fifty years later, it is clear that both measured and aggressive approaches contributed to positive change for First Nations people. But the 1970s was a difficult decade to be an Aboriginal person working collaboratively with powerful white conservatives. Neville was never the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, yet he was pursued for public comment on Aboriginal issues throughout his career. From January 1972, the media portrayed militant activists as the central figures at the Tent Embassy on Canberra’s King George Terrace, about fifty metres from the front steps of Neville’s workplace, Parliament House. Reporters delighted in winkling opposing comments out of the moderate Senator Bonner and the firebrands encamped across the road. In July 1972, a period of violent battles between the ACT police and occupants and demonstrators a Tent Embassy, Neville was reported as warning of an ‘upsurge of Black Power violence in Australia.(13) (Three years later, he spoke in the Senate of the ‘Trotskyists and other elements who have taken over the Aboriginal movement . . . [giving] firearms and hard drugs to young Aborigines.’)(14) Brisbane-based Pastor Don Brady, a Kuku Yalanji man and Neville’s close contemporary, encouraged young Queenslander Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to travel to the Embassy. Brady told the Bulletin ‘Look, about half a dozen Aborigines in Queensland have any confidence in [Neville Bonner]. He’s a party man.’

Written by Dr Sarah Engledow (born on Ngunnawal land, of English and German cultural heritage), Senior Research Curator, Museum of Brisbane.

Museum of Brisbane respectfully acknowledge Warunghu, Aunty Raelene Baker’s insight, conversation and participation in developing this series.

Footnotes

(5) For broader context see Sarah Maddison, ‘White Parliament, Black Politics: The Dilemma of Indigenous Parliamentary Representation’, Australian Journal of Political Science, vol 45 No 4 Dec 2010, 663-680.

(6) Jim Tucker, ‘Flashback 1971’, http://www.rugby.com.au 18 September 2021, accessed 13 Feb 2023.

(7) Interview with Pat Shaw. Bonner described Palm Island as a penal settlement in his Australian Story documentary, 1992.

(8) Tim Rowse, Senate Biographical Dictionary; Sarah Collard, 2021, ‘Fifty years since Neville Bonner broke new ground’, accessed 2 Mar 2023, https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/fifty-years-since-neville-bonner-broke-new-ground/w3tiun5xu

(9) Gary Foley, ‘Black Power in Redfern 1968-1972’, Redfern School of Displacement, http://www.kegdesouza.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Redfern-School-of-Displacement-Publication-web.pdf

(10) See footage of the late Dennis Walker in a documentary by Frances Peters Little at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yifkscay_sI&t=1098s

(11) David Harcourt, ‘Aborigines: a year of militancy?’, Bulletin, v. 194, no 4788, 8 January 1972, 9.

(12) Neville Bonner consistently referred to himself as an Aborigine. This and some other terms and phrases in this essay are drawn from the public language of the 1970s and 1980s.

(13) The Age, 21 July 1972.

(14) Quoted in Tim Rowse, ‘Out of hand: The battles of Neville Bonner’, Journal of Australian Studies 54-55, 1997: 96-107. Subsequent references to this article can say ‘Tim Rowse, ‘Out of hand’’.