Deep Reads Part Four: ‘You were worth it’, Neville Bonner 1983

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware this blog post contains images and references to deceased persons.

Neville Bonner’s parliamentary career ends, and his impact reverberates still.

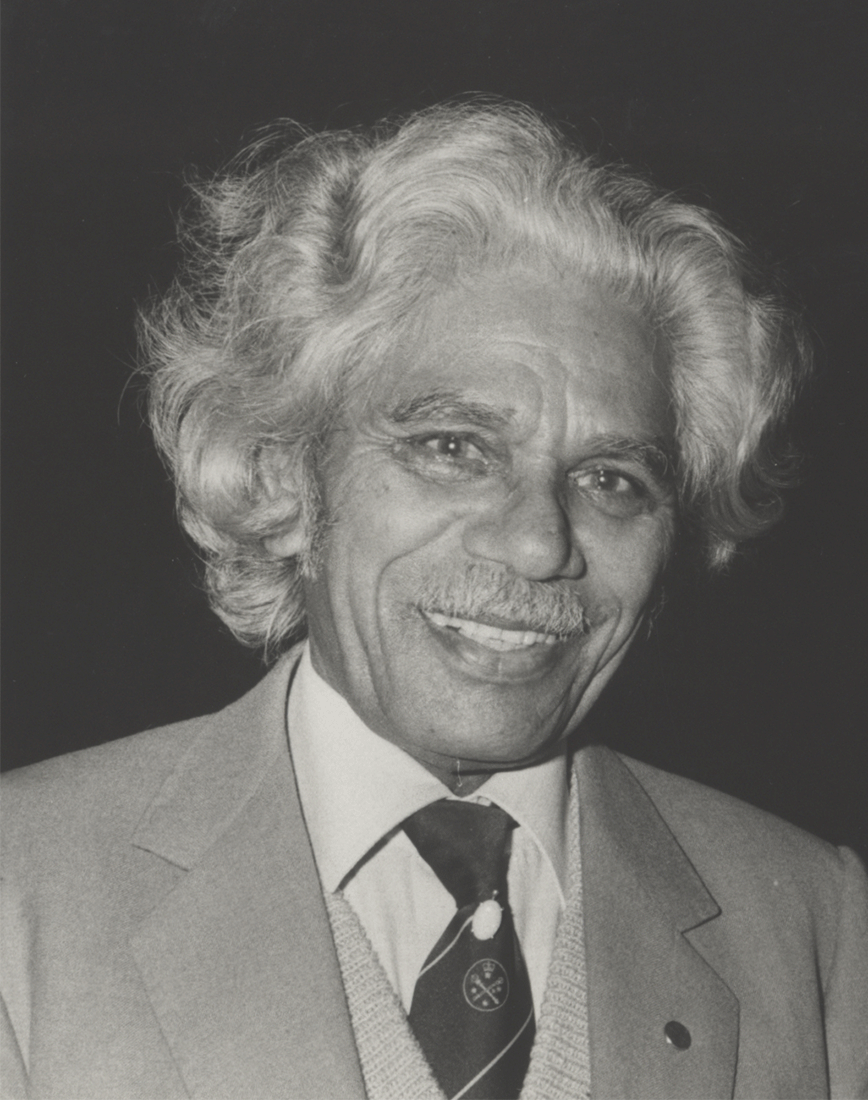

Neville Bonner was ‘dumped’ – at the instigation, he believed, of ‘power brokers’ within his party – in a turbulent political climate. On 3 February 1983, senior Labor Party figures gathered for the funeral of Brisbane-born prime minister Frank Forde at St Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church, St Lucia. Soon after the service they met for business. By nightfall Bill Hayden had been dropped as Labor leader and Bob Hawke installed. A double dissolution that Malcolm Fraser had hoped would take effect before Hawke became leader did not eventuate until 4 February. From that date, Neville’s senate seat was up for grabs. He went into preselection in early February 1983 as one of Queensland’s senior Liberal politicians. However, he had begun to sense that his old supporters were having trouble looking him in the eye. On 8 February 1983 he was relegated to third place on the Liberal ticket. His colleague Kathy Martin, dismayed, offered to swap her number 1 place for his; but Gary Neat was implacable: the ticket would not be changed. As Neville’s biographer Tim Rowse puts it, the state’s conservatives had ‘wearied of his independence of mind.’ (24)

On the night of 8-9 February, following the reveal of the Liberal ticket, Neville and Heather stayed the night at Brisbane’s Mayfair Crest. Unable to sleep, feelings of betrayal churning within him, he drew back the curtains in the early light and found himself looking down at the Roma Street Forum (now called Emma Miller Place). In his anguish, he thought of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their supporters gathered there; and found himself saying aloud ‘You were worth it.’ Over the coming days, his situation made front page news along the east coast as he and Heather ‘prayed and prayed’ and he ‘searched his soul’. Meanwhile, on 10 February it was reported that Joh Bjelke-Petersen had said Neville’s intervention in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander issues had ‘got out of hand and he had to go’. (25)

On Friday 11 February, Neville rang Malcolm Fraser to tell him he would run as an Independent. Fraser said that he greatly regretted what had happened. Neville ran a strong campaign but was not elected. Nor was Fraser. Neither man was to know that it was by no means the end of his working life; that further opportunities, honours, wisdom and recognition would come.

All people who were ‘firsts’ in the House of Representatives and the Senate play a symbolic and real role as ‘trailblazers’. It is astounding to reflect that after Neville Bonner, the next First Nations person elected to Federal parliament was Aden Ridgeway in 1999; and he, like Neville, was the sole First Nations person in parliament for the full course of his term. It is the fate of those who come first to be remembered principally for that; the years erase individual qualities, historical circumstances and the human struggles that arise from their collision. Yet Neville, raised by a riverbank, was a man of steel. Late in his life, he replied fierily, yet with his customary blend of carefully chosen, measured and courteous words, to a question put to him: of whether he had been a ‘token’ candidate for the liberal party.

I am no token . . . I never was and I never will be, for anyone, in a political party or in any other situation. I am Neville Bonner, proudly an Aborigine and proudly a member of this Australian community. I am a token for no person.

In the 47th Australian Parliament, there are 11 First Nations members. In 2021, on the fiftieth anniversary of Neville’s appointment to the Senate, Ken Wyatt, the first Indigenous person to be elected to the House of Representatives and the Minister for Indigenous Australians, paid tribute to his journey and his legacy, stating ‘He did it alone, he was tough but he was good’. Linda Burney, Minister for Indigenous Australians since mid-2022, honoured and encompassed his life perfectly when she said on the same occasion that he must have felt extremely challenged, and felt very lonely – but ‘what a magnificent and dignified man.’

Written by Dr Sarah Engledow (born on Ngunnawal land, of English and German cultural heritage), Senior Research Curator, Museum of Brisbane.

Museum of Brisbane respectfully acknowledge Warunghu, Aunty Raelene Baker’s insight, conversation and participation in developing this series.

Footnotes

(24) Emeritus Professor Tim Rowse, email to the author, 22 May 2024.

(25) This reference comes from Tim Rowse, ‘Out of hand: The battles of Neville Bonner’, Journal of Australian Studies 54-55, 1997: 96-107.

Neville Bonner consistently referred to himself as an Aborigine. This and some other terms and phrases in this essay are drawn from the public language of the 1970s and 1980s.