Times change, but pots stay the same until they smash.

Archaeologists and historians like to interrogate pots for stories they can tell of their times. Ceramics can speak of the degree of sophistication of certain cultures, of the influences of trading partners and the melding of techniques following conquest, colonisation or annexation. Pots of antiquity are often named for periods corresponding to political regimes, for example the Ming Dynasty or the Edo Period; place-specific cultures, such as the Mochica; or places of manufacture, such as Corinth or Athens. When pots are unearthed far from where they were made, the challenge is to work out how they travelled.

Can we conjure any broad cultural narrative out of an object as familiar and modest as a stoneware pot made in Queensland in the 1970s? Sure we can!

This Shigaraki-style vessel with Stanthorpe feldspar grit in the clay body was made by master potter Errol Barnes. Born in Brisbane in 1941, Errol began general teacher training as a school leaver in Brisbane before a Queensland Department of Education grant allowed him to spend two years focused on art at the Central Technical College in George Street. There, he learned from two giant figures in the history of Australian ceramics, Carl McConnell and Milton Moon.

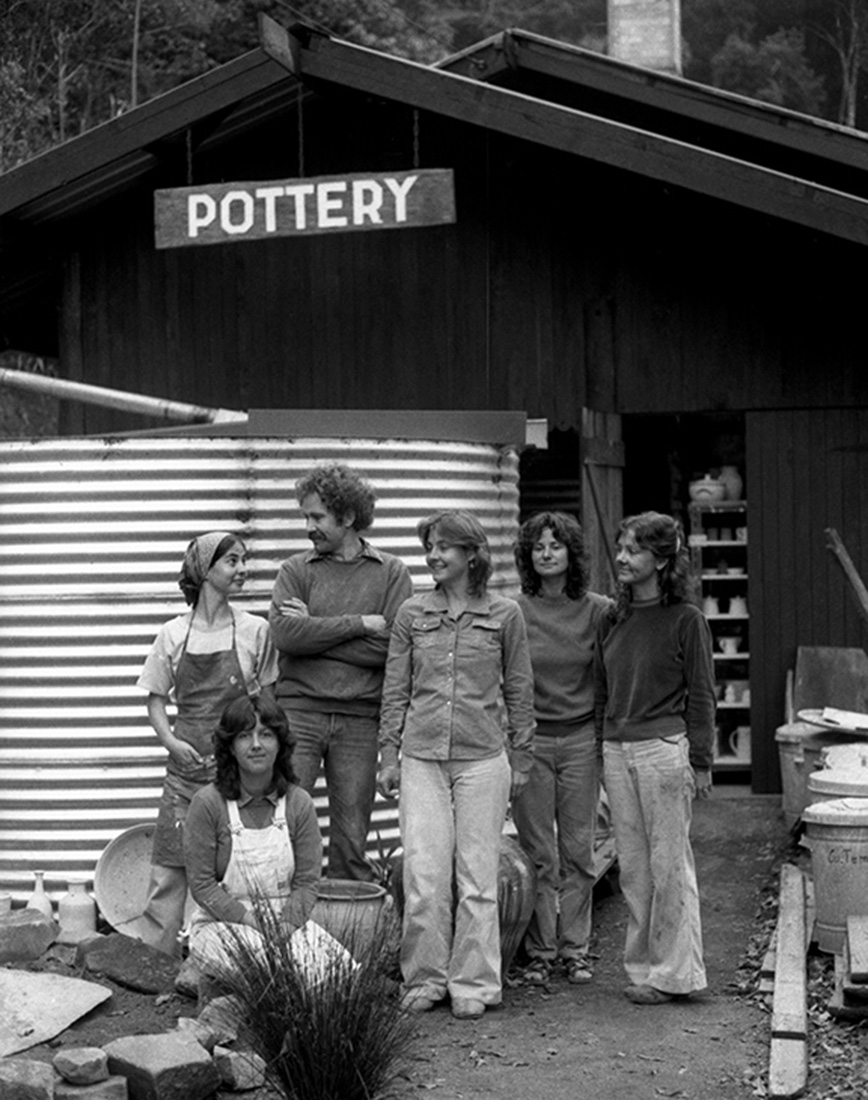

Becoming a full-time potter in 1965, Errol was one of the first artists to show with legendary art dealer Ray Hughes, whose Brisbane gallery opened in 1969. Errol worked in the city until the end of 1974, when he could afford to buy a rural block at Springbrook in the Gold Coast Hinterland. For the next six years, focused on building up his Lyrebird Ridge Pottery, he lived in a shed built from packing cases and salvaged timber with shutters for windows. In the 1980s, he got around to building the house he’s lived in ever since. For a while, he and his wife Fiona ran a rainforest café. In 2000, they created a snug habitat for the glow-worms endemic to the area, around which they developed a thriving eco-tourism enterprise.

Soon after Errol turned professional, in 1967, the Coalition government of Harold Holt established the Crafts Council of Australia, ushering in a fabled golden age for Australian potters, weavers, glassblowers, leatherworkers, jewellers and woodworkers. A Committee of Enquiry into the Crafts in Australia was initiated during the prime ministership of William McMahon in 1971. Within weeks of the Labor victory at the Federal Election of December 1972, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam personally announced the expansion of the Committee, in recognition of ‘the special pleasure which the crafts bring to thousands of Australians . . . Many young people who seek beyond the pressures and products of modern urban life a more personal and satisfying lifestyle are particularly attracted to them.’

In 1973 the Australian Council of the Arts was divided into seven boards, one of which was the Crafts Board. Its objective was to implement a Government Act to foster development of the crafts in Australia ‘for the benefit of craftsmen and the community in general.’ The Crafts Board sought to promote standards of excellence in the crafts; to widen access to and understanding of the crafts in both urban and rural areas; and to see an ‘Australian identity’ established through the crafts.

What did this look like in practice? Organisations were helped to purchase equipment and undertake workshops and special projects; craftspeople-in-residence were funded for institutions and community organisations; State and regional galleries were enabled to purchase craft works; proficient craftspeople were funded to undertake advanced study and workshop upgrades; and master craftspeople were paid to take on trainees, who were themselves provided with living allowances.

From 1976 well into the 1980s, Errol Barnes personally, and the Australian ceramics community more broadly, benefited from Errol’s responsibility for a series of students with financial support from the Crafts Board of the Australia Council. They included Martin Kelly, Monica Breeden, Fiona Buckley (who later married Errol), Michaela Kloeckner and Cameron Williams (who, at 24, was commissioned to make more than 200 pots, some astoundingly large, for Canberra’s new Parliament House). Other, self-funded students included David Usher. In the late 1980s, Ray Hughes, by then had moved from Brisbane and was based in Sydney, introduced Errol to several of the painters he represented, hoping that collaboration would ensue. It did. Vessels from that period, thrown by Errol and decorated by artists including Queenslanders William Robinson and Joe Furlonger, are in major Australian collections including Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, the National Gallery of Australia and the National Gallery of Victoria. In a gracious gesture, one of Errol’s pots in the collection of HOTA, Gold Coast, was gifted in 1995 ‘by the citizens of the Gold Coast to future generations’.

Given that Errol has always lived in Queensland, it is a curious fact that nationally, his work is best represented in the collection of the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA). For decades, Errol did not know why; but this is the story. His pieces were part of The Potter’s Art, a Crafts Board exhibition that toured Australia in 1981-1982. Late in the Coalition prime ministership of Malcolm Fraser, in mid-1982, it reached Perth. Curator of Craft Robert Bell urged the acquisition of the entire exhibition for AGWA, as it was a ‘good and typical cross-section of the current activity in the domestic ceramics area’. The extraordinary acquisition went through in 1983. It was a heady year for Perth all round: Malcolm Fraser’s having lost office to Bob Hawke in March, Australia won the America’s Cup in September and Hawke, vigorously celebrating at the Royal Perth Yacht Club, declared that “any boss who sacks a worker for not turning up today is a bum”’.

Civilisations rise and fall. So does the popularity of ceramics. It is up to museums to ride out such fluctuations and continue to excite people about them later.

What about you? Do you have a pot that can tell you a lot?

Share your story with us on Instagram or Facebook by tagging @museumofbrisbane.

Love ceramics? Don’t miss your chance to visit Clay: Collected Ceramics before it closes on 22 October 2023.