Deep Reads Part One: The Early Experiences of Neville Bonner 1922-1969

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware this blog post contains images and references to deceased persons.

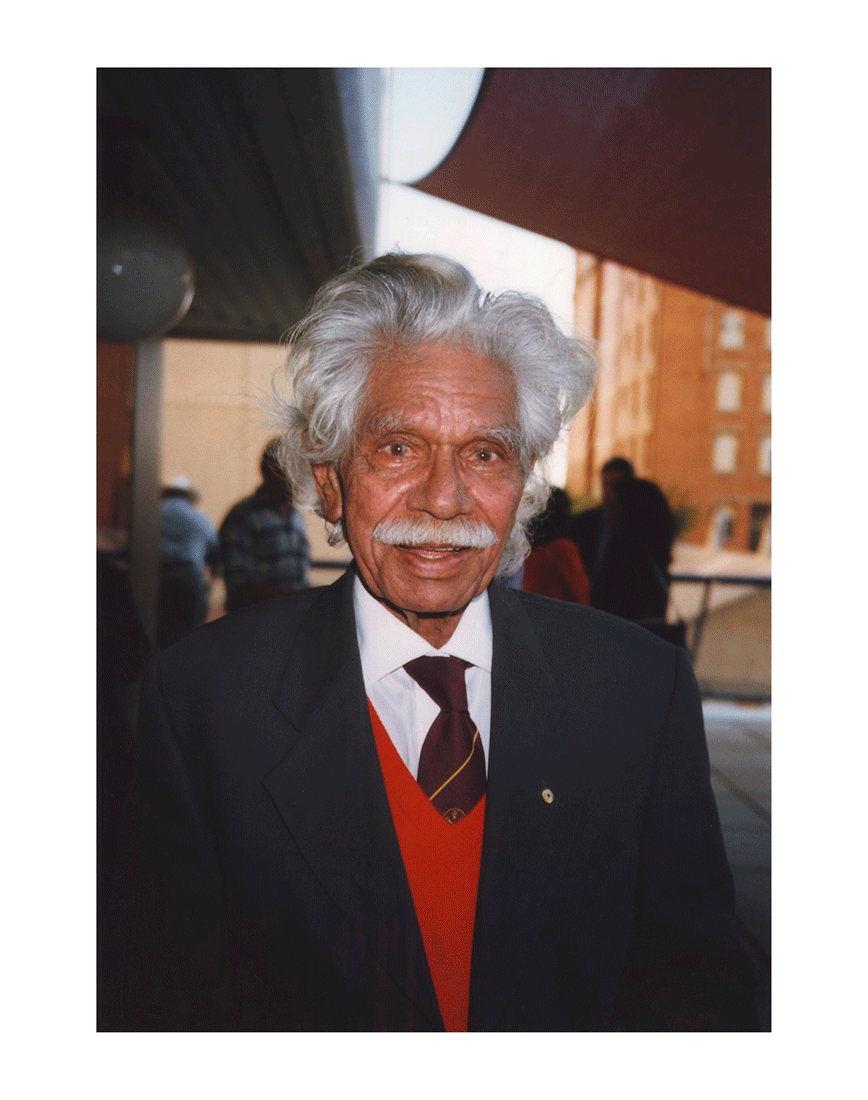

In the early hours of 9 February 1983, a sleepless man stood at the window of a high room in Brisbane’s Mayfair Crest Hotel. Drawing the curtains aside he looked down and saw the Roma Street Parklands, empty in the soft dawn light. His mind flew to a day four months before, when the Forum had seethed with chanting protesters, shouting orators and knots of policemen, and he, a Jagera man, Senator Neville Bonner, had sat cross-legged on the ground in their midst and sung a dirge of mourning.(1) None of the white people and few of the young First Nations people around him had ever heard such a sound, he assumed; but he had heard elders singing that way when he was a teenager and he said it ‘tore to the depths of his soul as an Aborigine’ when sang that way as a man.(2)

The recollection of that intense, revelatory moment by the window in the hotel on the corner of Ann and Roma Streets stayed with him.

Neville Bonner AO (1922–1999), senator for Queensland from June 1971 to February 1983, is honoured world-wide as the first Aboriginal Australian person to be elected to federal parliament. (3) A resident of Ipswich from the beginning of the 1960s, while in Brisbane Senator Bonner worked in the Commonwealth Parliament offices, then located at 295 Ann Street. Later, when he was Chair of the Queensland Indigenous Advisory Council, his office was at Enterprise House at 46 Charlotte Street. Brisbane’s Neville Bonner Bridge, set to open in 2024, is just the latest of many places and structures in Australia named for him, including, in Brisbane, the Neville Bonner Building (demolished in 2017) and the electoral division of Bonner. The Neville Bonner City Cat, launched in 2020, flies the Aboriginal flag as it plies the waters of the Brisbane River.

Today, few Australians know much more about Neville Bonner’s place in Australian history than his status of one of the country’s ‘firsts’. Yet Bonner was a resourceful, resilient and hardworking individual with a fascinating life story, whose career in a suit took place during a time of tumultuous change in Australia. He deserves to be remembered for more than his name.

A surprising number of Australian parliamentarians, past and present, experienced remarkably tough childhoods. Few, probably, were as tough as Neville Bonner’s. Talking with Pat Shaw when he was in his early 60s, he recalled that his mother, an Aboriginal woman from Deebing Creek, Ipswich, gave birth to him on a government-issue blanket under a palm tree on Ukerebagh Island, at the mouth of the Tweed River in northern New South Wales. He described the settlement there as an ‘awful place’ frequented by white people of the worst kind. As a boy Neville went with his family to join his grandparents at Lismore, where they lived by the Richmond River in a structure his grandfather had built from salvaged materials. Neville was largely educated by his grandmother, only attending school for a year at Beaudesert in his mid-teens. Henceforth he worked in labouring jobs including ringbarking, cane cutting, scrub clearing, herding stock and dairying.

In the late 1930s, while working near Hughenden, Queensland, Neville met and married Mona Banfield. When racially abused by her white employer, Mona retaliated; she was sent to Palm Island (where, as it happened, she had been born). After Palm Island (now known as Bwgcolman) was declared a reserve and penitentiary in 1914, people from many different Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations were forcibly removed from their traditional lands and taken there. Neville joined Mona there in the mid-1940s, initially for the twelve-month period of her sentence, but the couple was to live there for fifteen years, during which they had five sons and Neville began his involvement in community affairs as a founding member of the Palm Island Social and Welfare Organisation. By the time they left the settlement, Neville was its assistant works overseer.

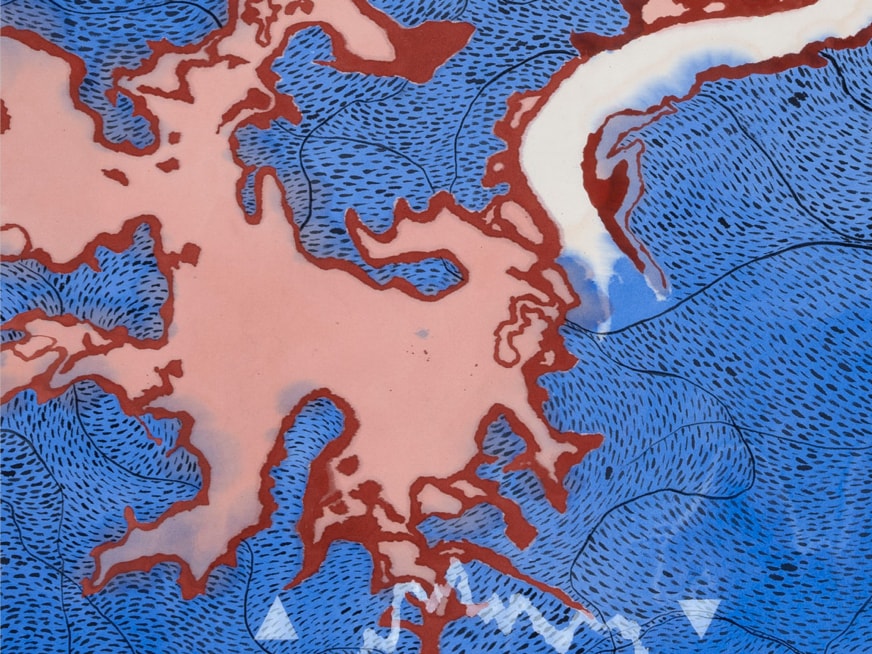

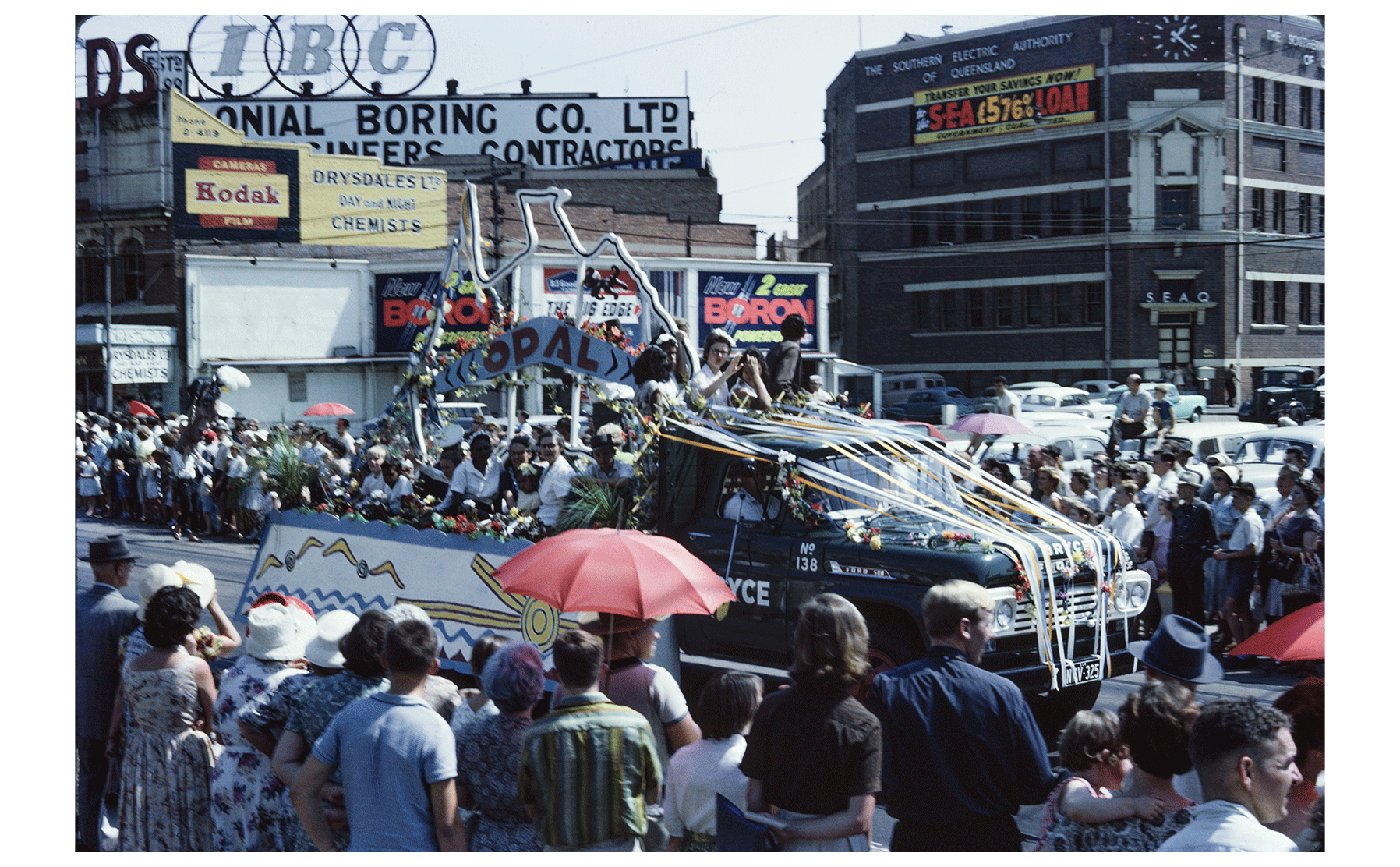

Living in Ipswich from 1960, the Bonners soon joined the new One People of Australia League (OPAL). More moderate than the Queensland Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders – seen, by some, to be under considerable Communist Party sway – OPAL was broadly focused on the positive influence of school education and committed to working within existing political structures to bring about change. While OPAL was not a religious organisation, many of its members were practising Christians. Neville Bonner became OPAL’s Queensland President in 1968 and remained so until 1974.

In 1969, when Neville was working as a bridge carpenter for Moreton Shire Council, Mona Bonner died. As a widower he became increasingly close to a fellow member of OPAL, Heather Ryan, who was the granddaughter of a pioneering Queensland Anti-Socialist Party and Liberal politician and described herself as a white Presbyterian and grammar-school girl. (4) (Such were the norms of the time that she was nervous about telling her father that she was seeing Neville, but his only objection was that Neville was a practising Catholic.) By way of discussions and debates with Heather’s daughter and son-in-law, who were Liberal Party members, Neville attended his first branch meeting. Incensed by a personal remark by Bill Hayden, then the Member for Oxley, later the leader of the Labor Party (and ultimately Australia’s governor-general), Neville joined the Liberal Party in May 1967 and by 1969 was a member of its Queensland executive.

Written by Dr Sarah Engledow (born on Ngunnawal land, of English and German cultural heritage), Senior Research Curator, Museum of Brisbane.

Museum of Brisbane respectfully acknowledge Warunghu, Aunty Raelene Baker’s insight, conversation and participation in developing this series.

Footnotes

(1) In an interview with Pat Shaw in the National Library of Australia which provides fundamental source material for this essay, Bonner recalled the date as 8 April, but research indicates that it must have been the night of Tuesday 8 February, the day Bonner learned he had been relegated to third place on the Liberal Party Senate ticket for Queensland. Similarly, the day he announced he would run as an Independent was Friday 11 February, not 11 April as he recalled. The Federal election was on 5 March 1983. Bonner, Neville, 1922-1999 & Shaw, Pat & Australia. Department of the Parliamentary Library. 1983, Neville Bonner interviewed by Pat Shaw in the Parliament’s oral history project [sound recording]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-217919415The authoritative short written account of Bonner’s life and career is Tim Rowse, ‘Bonner, Neville Thomas (1922-1999)’, The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, Online Edition, accessed 20 June 2023, https://biography.senate.gov.au/bonner-neville-thomas/

(2) Neville Bonner consistently referred to himself as an Aborigine. This and some other terms and phrases in this essay are drawn from the public language of the 1970s and 1980s.

(3) David Kennedy was ALP member for Bendigo from 1969 to 1972, but his Palawa heritage was not publicly known and he is not known to have identified as Aboriginal at the time he was elected.

(4) See ‘All Their Own Work’, Bulletin vol 103 no 5353, 22 Feb 1983, 116; Museum of Australian Democracy, ‘From the Oral History Collection: Heather Bonner’ (Heather Bonner interviewed by Michael Richards), https://www.moadoph.gov.au/blog/from-the-oral-history-collection-heather-bonner/