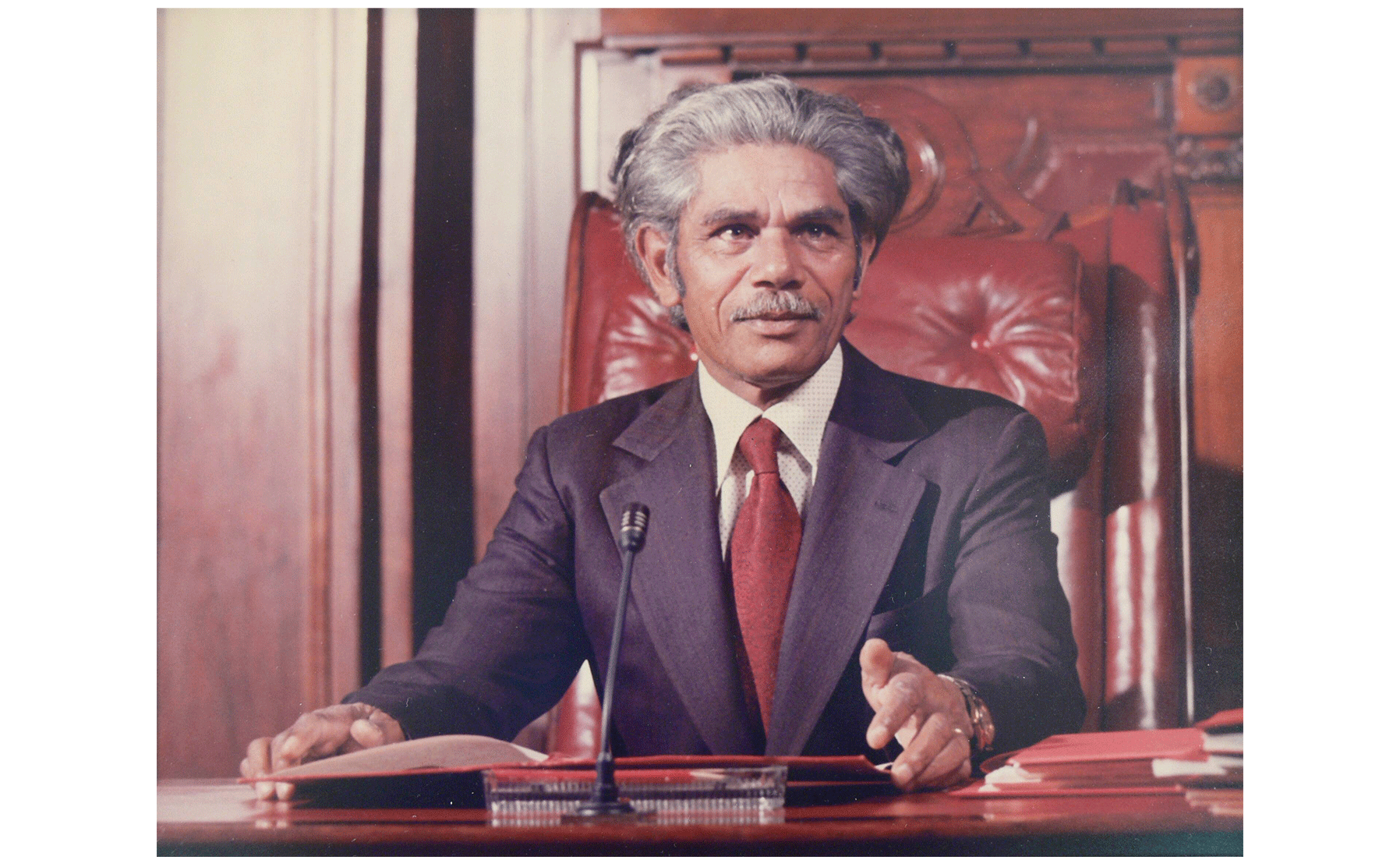

Deep Reads Part Three: A Balancing Act in Canberra, Neville Bonner 1976-1982

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware this blog post contains images and references to deceased persons.

Having settled into his role of Senator, Neville juggled his party allegiance, the responsibility he felt toward all Aboriginal Australians, his personal beliefs and the need he felt to demonstrate interest in the great variety of issues before Parliament.

Neville Bonner’s dedication to the Liberal party notwithstanding, over the course of his 12 years in Parliament he crossed the floor to vote against them 34 times.(15) The first time, in 1976, when he voted against the abolition of a $40 government contribution to the cost of pensioners’ funerals, the Bulletin noted ‘Neville Bonner . . . has no history of fierce independence . . . but he is now showing some backbone and could go again on certain issues.’ Go again he did. Neville was to end his parliamentary career as the fourth-most frequent floor crosser in the Australian parliament between 1950 and 2019. (16) While statistics indicate that Liberals tolerate floor crossing better than their opponents (historically, Labor parliamentarians have crossed the floor far less often than conservatives) a floor crosser at best causes some embarrassment to their party and at worst, can be painted as a traitor. (17)

Neville’s speeches, questions and interjections – every word of which can be read on the website of the Parliament of Australia – demonstrate that Aboriginal issues were by no means his only interest over his twelve years in the Senate. He explained later that as the ‘new boy’ he had had to establish himself as ‘a person who was able to make a contribution toward parliament as a whole’. (18)Yet his passionate, articulate advocacy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights shone through from the beginning. While he told reporters that the Tent Embassy demonstrators did little to [enhance the image of Aboriginal people], he sympathised publicly with what they were protesting about, telling Parliament that the people there ‘were demonstrating against all the things that have happened over the years – the shootings, the killings, the taking of the land.’ Such words and concepts – now simply called the truth – were rarely part of mainstream conservative discourse in Australia in the 1970s.

Toward the end of his life Neville reflected that having ‘established his bona fides’ in parliament, he was ‘able to come out on different issues in a more forceful . . . perhaps a little more radical [way]’. As early as 1974 he moved a motion acknowledging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the original owners of the continent and urging the government to pay compensation for their dispossession. A private senator’s bill he introduced in 1976, the Aboriginal and Islander (Admissibility of Confessions) Bill, did not advance far at the time, but it has been credited as an early step on the path leading to the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody from 1987. (19) Appointed Chair of the Select Committee on Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in 1976, and the Joint Select Committee on Aboriginal Land Rights in the Northern Territory in 1977, in 1979 he introduced legislation to establish the Aboriginal Development Commission, to ‘place into Aboriginal people’s hands important instruments for . . . policies of self-management.’

Along with environmentalist Harry Butler, Neville was Australian of the Year in 1979. The fourth Aboriginal person to hold that title, he was the first sitting politician to become Australian of the Year (a much less high-profile appointment than it is now, calling for few public appearances or speeches on behalf of various causes).

Neville’s position in the first week of October 1982, as Brisbane played proud host to the Commonwealth Games, is painful to imagine. A major Land Rights march was planned for 7 October. Although he agreed with the principles behind the demonstration, he feared it would get out of hand, putting many First Nations people in danger. He could scarcely stay away; so he chose to attend and urge peaceful protest, notwithstanding that event organisers, the Black Unity Committee, had already called for the same thing. (Non-Indigenous activist and Uniting Church minister Noel Preston wrote in his diary that ‘Senator Bonner’s reported comment that the illegal demonstrations were inspired by ‘non-Aboriginals’ sadly reflects how out of touch he was.’) (20) Vintage footage shows Neville addressing the throng: ‘March by all means – but do it in a way that no one can come back at you because we are law abiding citizens . . . and we will do it with a cause that is something much deeper.’ (21) Ultimately, he sat down on the ground of the Roma Street Parklands (itself a traditional gathering place for contests amongst young Aboriginal initiates from around the region) and chanted the dirge he first heard, perhaps, as a teenager at Woorabinda. (22)

It is doubtful that there was any report of exactly what Neville said, and newspaper images could not speak of the complexity of his situation. Photographs simply show one of the best-known Aboriginal people in Australia, surrounded by shouting crowds, banners and scores of policemen. (23) Neville recalled that the director of the Liberal Party in Queensland, Gary Neat, wrote to him to commend his actions on the day. However, before six months were out the Tribune – official newspaper of the Communist Party of Australia – ran a picture captioned ‘Senator Neville Bonner marching in Brisbane . . . It was his support of the Black Protest that led the Queensland Liberal Party to dump Bonner.’

Written by Dr Sarah Engledow (born on Ngunnawal land, of English and German cultural heritage), Senior Research Curator, Museum of Brisbane.

Museum of Brisbane respectfully acknowledge Warunghu, Aunty Raelene Baker’s insight, conversation and participation in developing this series.

Footnotes

(15) He stated in Australian Story in 1992 that he crossed 23 times, but Parliamentary records say otherwise.

(16) Deirdre McKeown and Rob Lundie, ‘Crossing the floor in the federal parliament 1950-April 2019’, Department of Parliamentary Services Research Paper Series 2019-20, Research Paper 12 March 2020, p 20.

(17) See ‘Crossing the floor’, https://peo.gov.au/understand-our-parliament/how-parliament-works/parliament-at-work/crossing-the-floor/

(18) Australian Story documentary, 1992.

(19) Tim Rowse, Senate Biographical Dictionary; Sarah Collard, 2021, ‘Fifty years since Neville Bonner broke new ground’, accessed 2 Mar 2023, https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/fifty-years-since-neville-bonner-broke-new-ground/w3tiun5xu

(20) See ‘Peter’s Verdana’, http://radicaltimes.info/PDF/photos1982.pdf accessed 24 Mar 2023.

(21) The film is by Lachlan Hurse and is on Youtube. https://workersbushtelegraph.com.au/2012/08/25/1982-commonwealth-games-land-rights-protests/. Bonner appears at the 19 minute mark.

(22) For information on the Roma Street Parklands as a gathering place for First Nations people of the region see Ray Kerkhove, Aboriginal Camp Sites of Brisbane 2015, 99-101. I speculate on Bonner’s memory of the mourning chant from my reading of Rowse’s Senate biography, which states that Bonner saw tribal ceremonies for the first time at Woorabinda.

(23) A photograph of Bonner being photographed by ‘the media’ is by Bob Weatherall at http://radicaltimes.info/PDF/photos1982.pdf

Neville Bonner consistently referred to himself as an Aborigine. This and some other terms and phrases in this essay are drawn from the public language of the 1970s and 1980s.