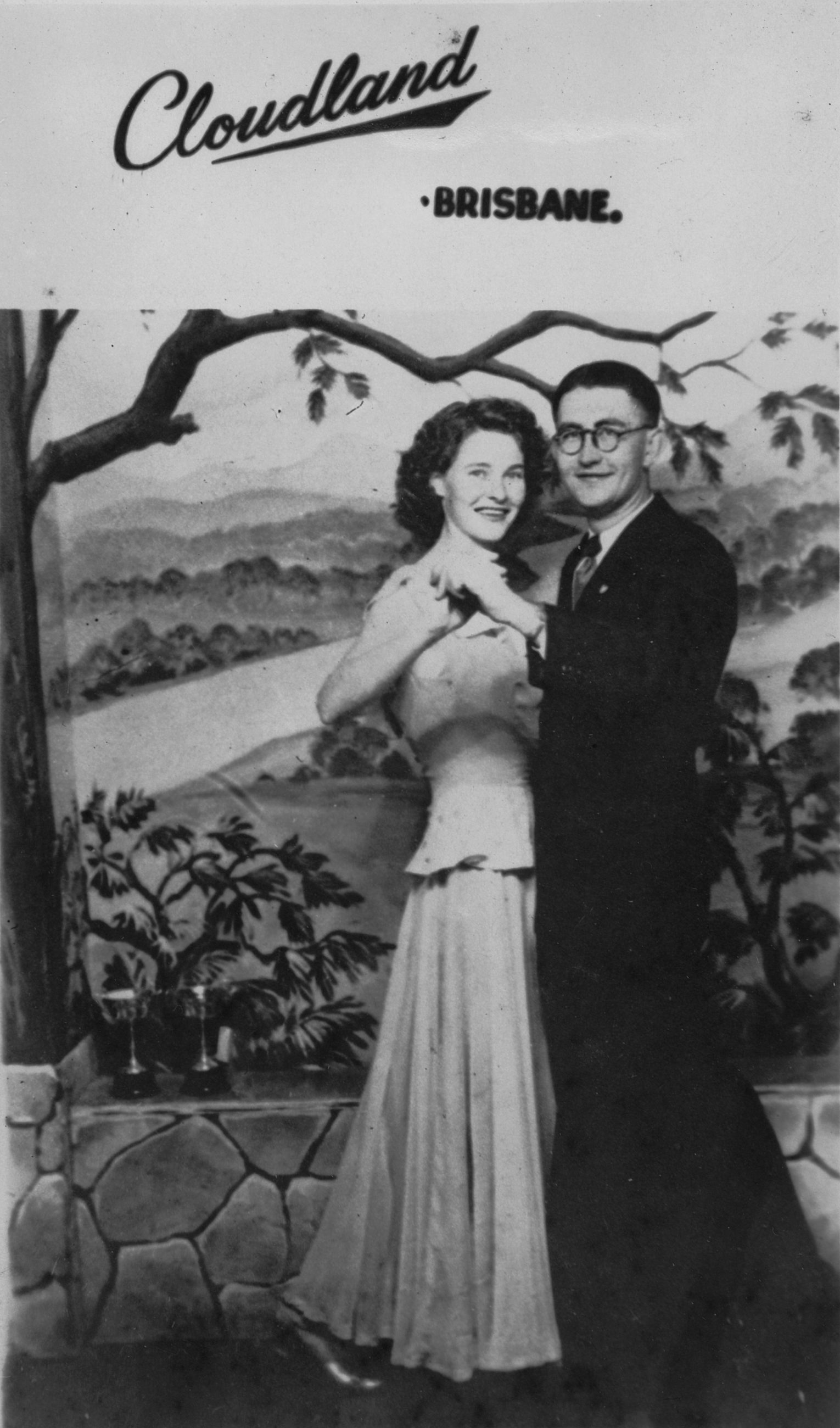

One of Brisbane’s long-lost loves, Cloudland Ballroom remains the scene of many a meet cute, first kisses and declarations of being together forever and ever.

The iconic dancehall was dreamt up by construction engineer TH Eslick, also responsible for the development of Melbourne’s Luna Park and Sydney’s White City Amusement Park. Eslick’s grand plan was to build Brisbane’s own Luna Park. Construction began in 1939 at an enviable site perched high among the trees in Bowen Hills in Brisbane’s inner-north. Of this undertaking, Eslick remarked:

“I have finished with wandering around the world and all I want to do now is to build this last amusement park in your beautiful city and end my days here in your glorious sub-tropical sunshine.”

The Telegraph, Brisbane, 23 March 1939.

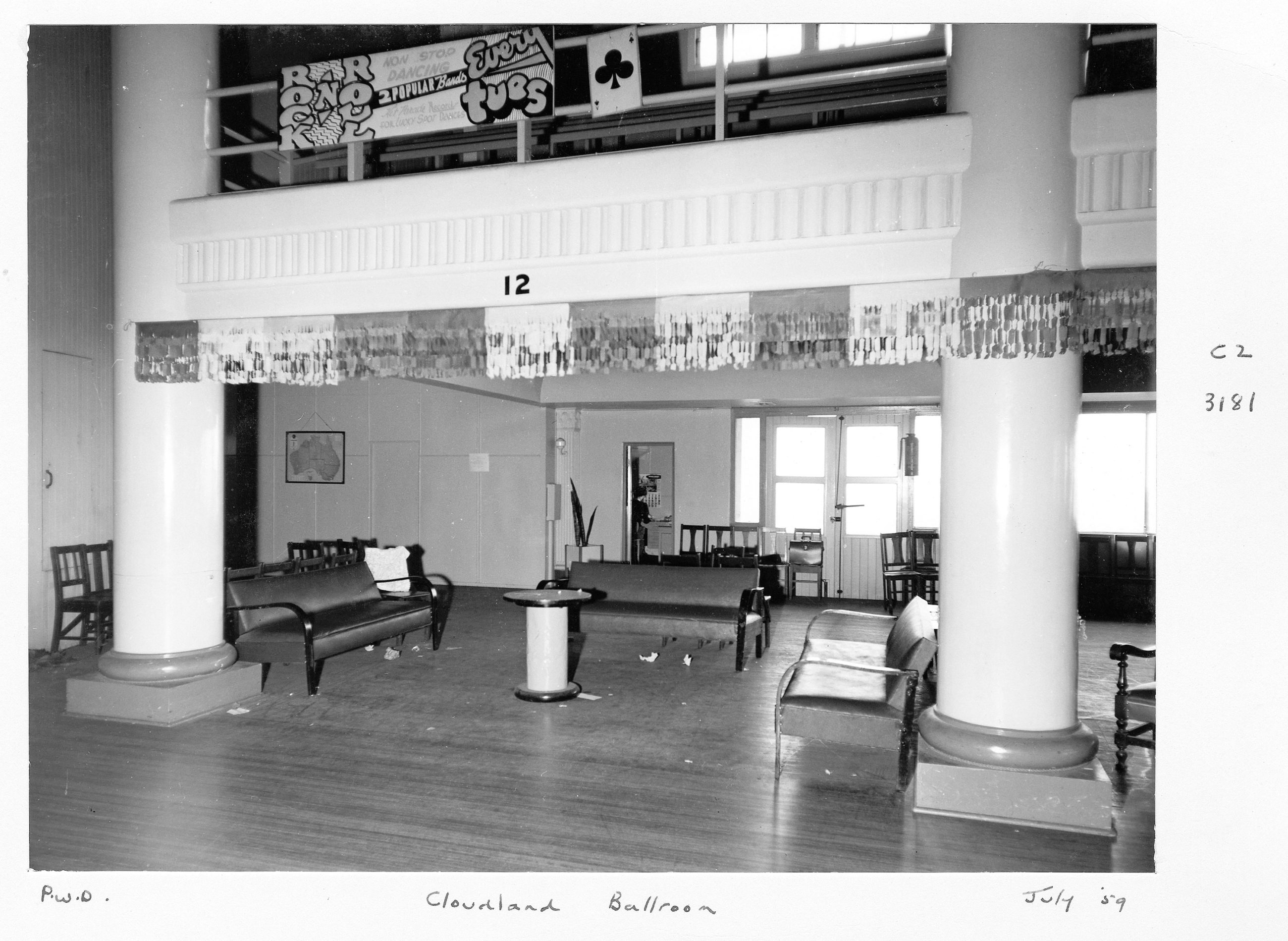

Come mid-1940, there was no fun park as Eslick had intended though there was lavish ballroom with an inaugural ball held on 2 August. A funicular railway car carried excited evening revellers from Breakfast Creek Road up the steep hillside, so they could save their energy for the huge 46 by 22 metre ‘sprung’ dance floor – the biggest in the country.

The spotted gum floorboards had not long been buoying dancers when war loomed over Brisbane and Eslick left the city. In August 1942, US General Douglas MacArthur and his troops set up shop in the large, abandoned ballroom, dubbing it “Camp Luna Park”. In late 1946, the war had ended and Eslick had not returned. Before leaving the city, the US troops had one last mission, rebuilding the iconic dance floor as a gift to the people of Brisbane. Their efforts did not go to waste and it wasn’t long before the grand building was given a second lease on life.

One of Eslick’s previous projects – the La Monica Ballroom in Santa Monica, California, opened in 1924 – also possessed this springiness in its dance floor. Despite rumours of rubber tires or metal coils, Cloudland’s ‘sprung’ dance floor was constructed in a similar way to the La Monica Ballroom – with thousands of long, narrow, hardwood, tongue-and-groove floorboards. Maple was used in California, spotted gum in Queensland.

In Cloudland: Queen of the Dancehalls, James G Lergessner sites a letter written by Alistair Gow of Alex Gow Funerals. In this letter Alistair details a Saturday afternoon in the late 1950s at Cloudland. He had just finished a training session with Bill and Fay Johnston’s Dance Studio. They were allowed to use the ballroom for training in exchange for the dancers blowing up hundreds of balloons for that night’s festivities. On this particular Saturday afternoon, the door at the back of the stage that provided the only access to below the dance floor was left open and Alistair, an apprentice carpenter, went down for a closer look. He explains that, despite the construction of the floor being a fairly standard bearer and joist arrangement, the sheer length of the joists, the long tightly packed floorboards and a second layer of floorboards beneath, were likely what gave the dance floor its beloved bounce:

“Old, experienced carpenters who worked with tongue-and-groove floorboards will know that if you over-cramp a floor, particularly over large open areas, you can cause the bearers, floor joists and floor in the middle of the area being laid to rise and lift off the stumps. I believe it was this principle that [had] assisted in allowing the dance floor to flex and gave the impression it was on springs.”

Gow as cited in Lergessner, 2013, p. 143

Not long after the US soldiers had completed their work on the dance floor, the ballroom was purchased by sisters Mya Winters and Francis Roach. It was renamed the Cloudland Ballroom and once again opened to the public in 1947.

“Luna Park, most ambitious amusement centre ever established in Queensland, which failed because of conditions in the early part of the war, is to be sold by public auction on November 21.”

The Telegraph, Brisbane, 7 November 1946.

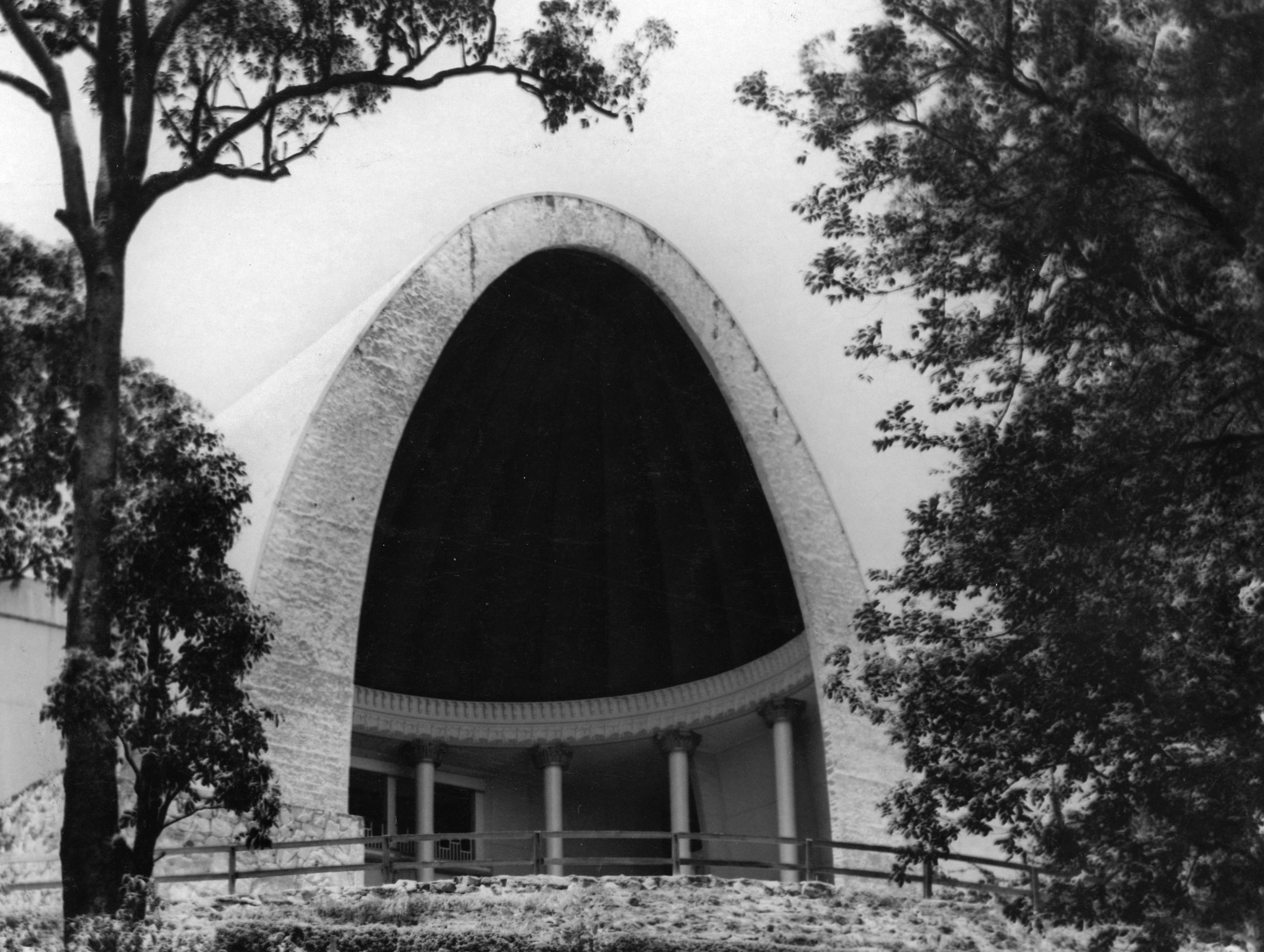

A sparkling social mecca for all of Brisbane, Cloudland hosted debutante and classical balls, school and university exams, school formals, as well as rock concerts and even markets. Its 18-metre-tall arched entrance presided over the city, beckoning people from miles around. And they came – to revel in its glory, gaze out over the sprawling city below and perhaps meet the loves of their lives.

Big Bands and jitterbug reigned supreme in the early 1950s, when crowds of more than 2,000 donned their best and headed for the ballroom on the hill. In 1958, Cloudland hosted three of Buddy Holly’s six Australian concerts. Other notable performances included those from The Clash, Echo and the Bunnymen, Simple Minds, Midnight Oil, Cold Chisel, The Angels, Bee Gees and Jerry Lee Lewis. In 1979, Queen Elizabeth visited the famous venue.

However, with the glitz came a less than glamorous maintenance bill and in the early 1980s, the building’s owner had spent several years funding extensive repairs. Despite cries from the public to maintain their beloved Cloudland, the city awoke on the morning of 7 November 1982 to find their nightmare realised – the grand arch had been knocked from the skyline, a mound of rubble in its place. With the Deen Brothers swinging the hammers, it remains one of the most memorable demolitions carried out during of the Joh Bjelke-Petersen government.

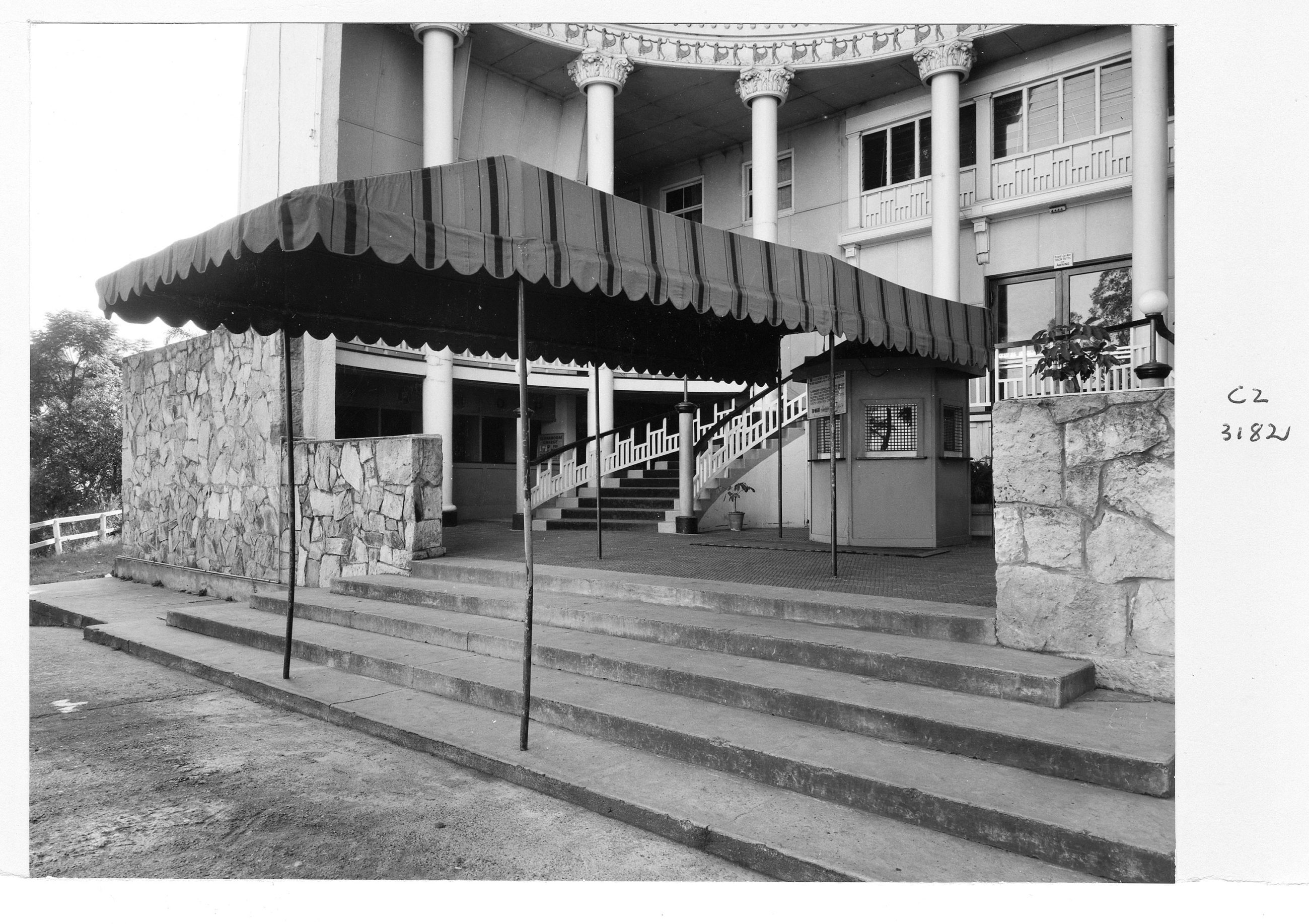

Cloudland’s memory lives on in the hearts of those who were fortunate enough to bounce around on its dance floor, twirl beneath its Corinthian columns and huddle around small timber tables in corners dimly lit by seashell-ensconced bulbs. The treasured venue bore witness to nearly four decades of shifting trends in music, dance styles and fashion statements, as well as sordid affairs, frivolous flings and the beginning of many great love stories.

Want to explore more of Brisbane’s history? Making Place: 100 Views of Brisbane presents 100 historical and contemporary depictions of the Brisbane region from the Museum of Brisbane Collections.