Interview by Louise Martin-Chew

Artist Judy Watson’s new book, women of brisbane, draws together stories of women, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, who have shaped Brisbane’s history. The book will be launched on International Women’s Day, and its narratives of Brisbane’s women, written by historians, writers, descendants and members of the community document, for the first time, the contributions of women to our city.

Judy Watson’s art practice draws on collective memory to reveal the human histories of individuals, the objects and the archive. Her public art in Australian cities and overseas uses site and memory to reflect on difficult subject matter from the past, transforming it into art objects that seduce the eye.

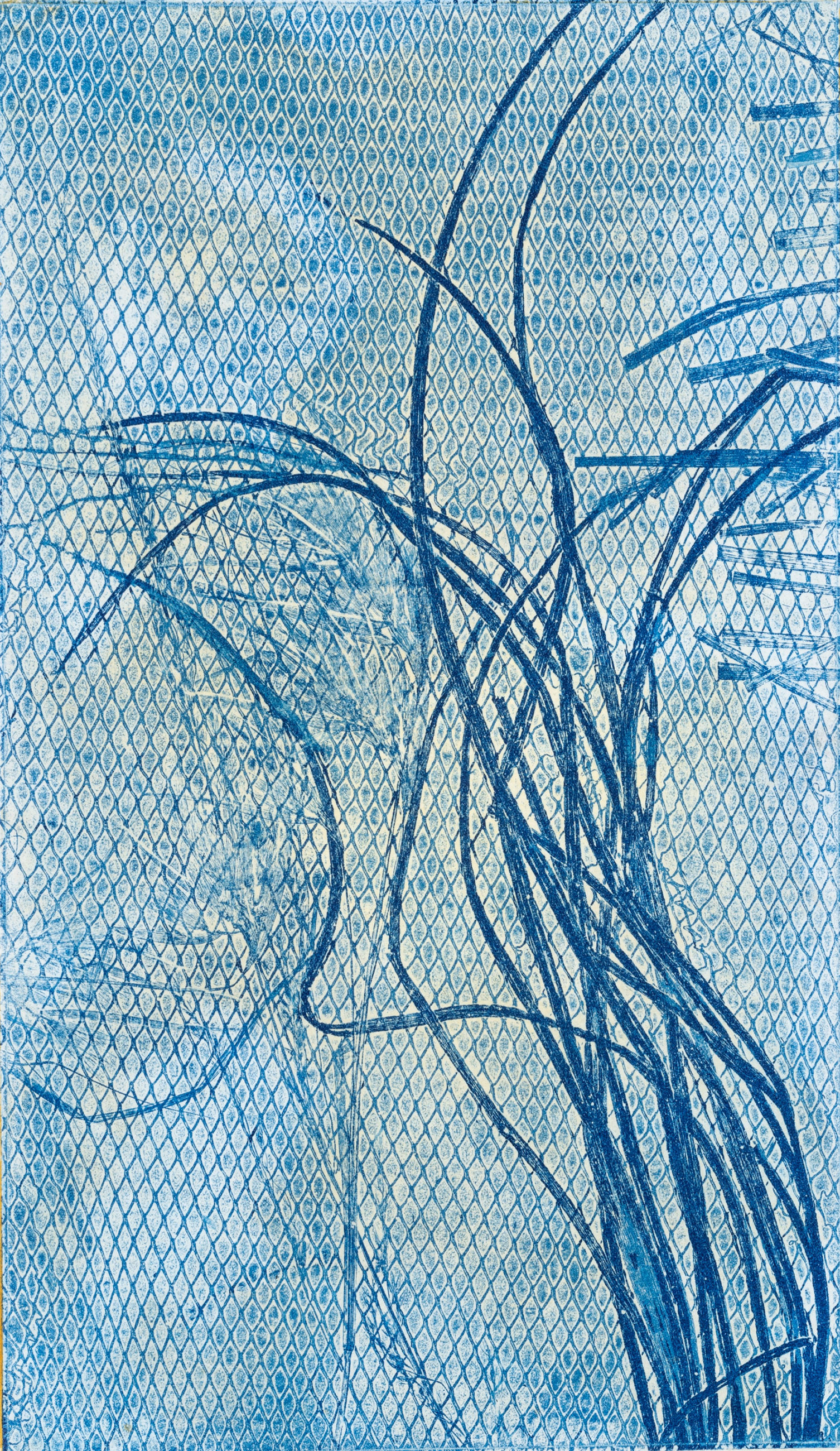

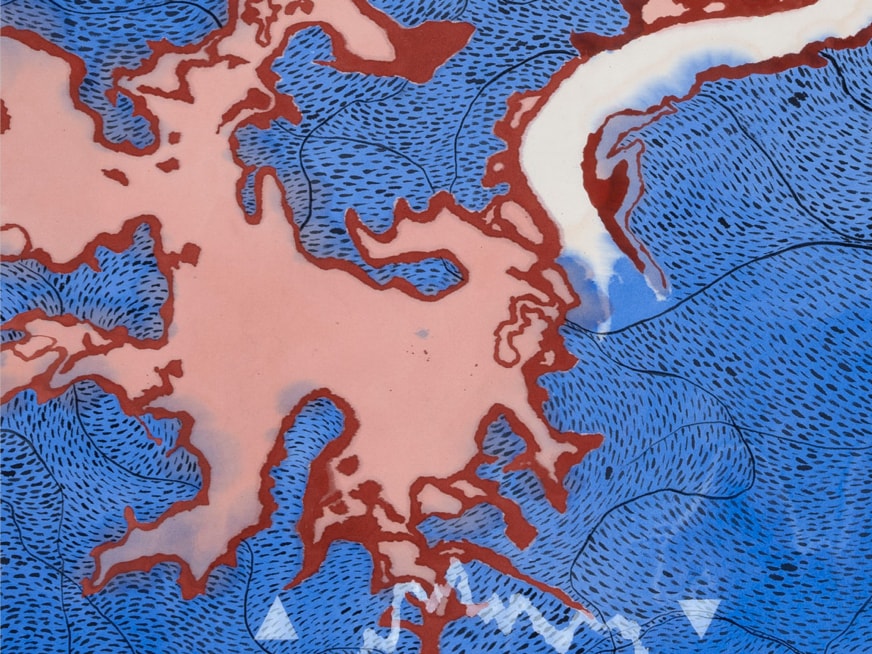

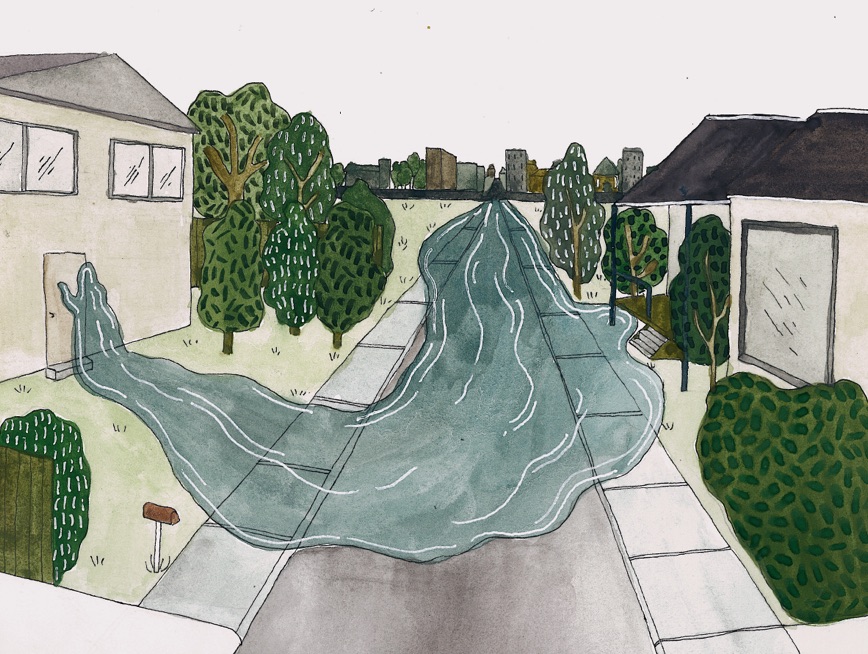

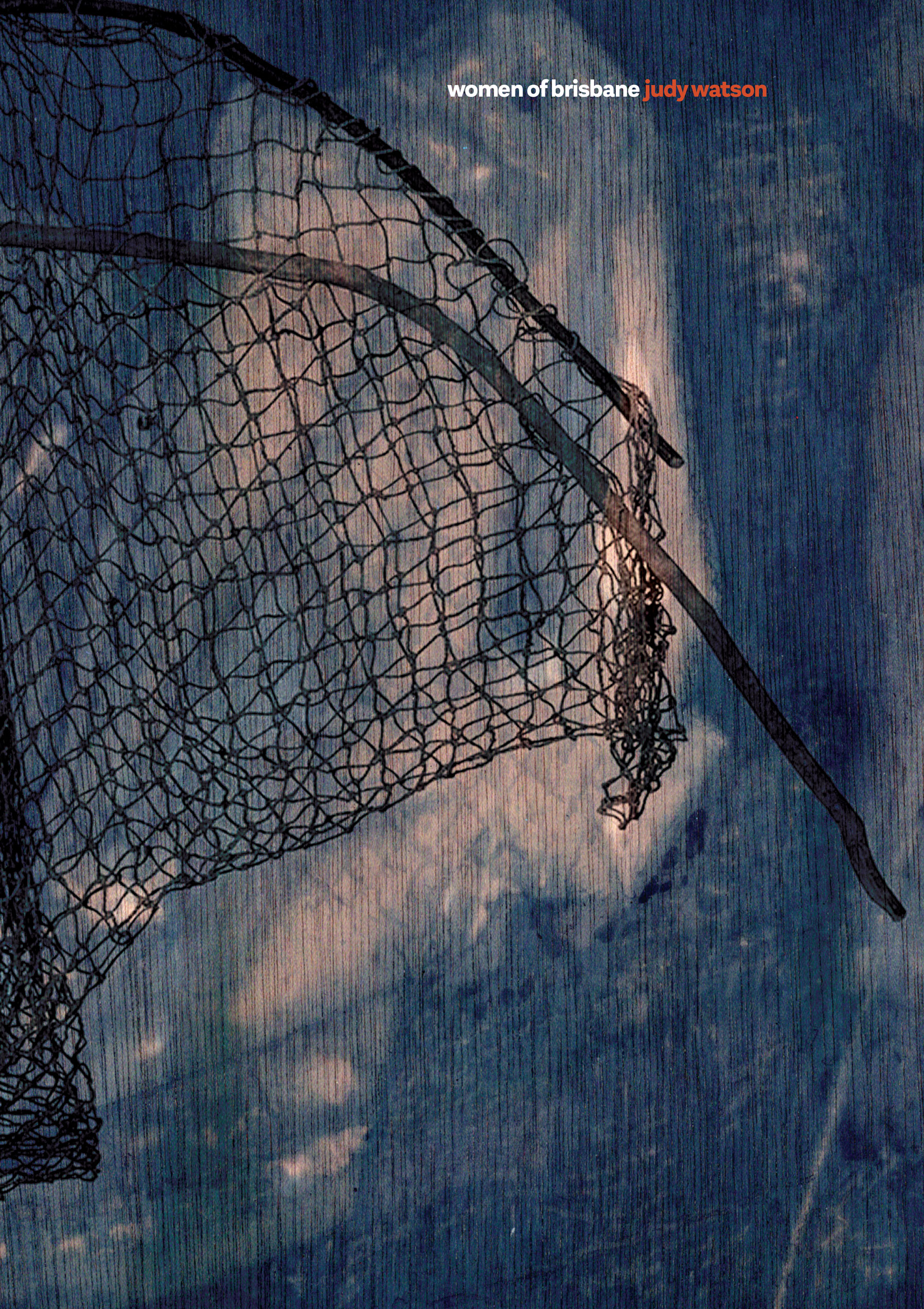

In Brisbane her work tow row (2016) stands in the Cultural Centre precinct at the door of the Gallery of Modern Art, with other major artworks in the Brisbane Magistrates Court and in the Turbot Street Underpass. Most recently Watson developed an evocative temporary artwork projected onto the cliffs at Howard Smith Wharves (late 2020). Called water under the bridge it explores narratives (Aboriginal and non-Indigenous) that have shaped the Brisbane River, and also reflects Judy’s Waanyi (running water) heritage. Adjacent to the river near the Hamilton Reach is a suite of artworks honouring Brisbane’s women and the Aboriginal histories of the area. This artwork, named bandarra-gan chidna: strong woman track / track of strong women (2019), is part of the Lores Bonney Riverwalk.

Judy’s process is consultative, and to find stories of over 180 influential women who have shaped our city, she engaged with historians and the broader Brisbane community who contributed the names and stories of women who would otherwise have remained hidden.

Judy has brought together the narratives of these women, together with the ecological histories of the area around Kingsford Smith Drive, in a new book titled women of brisbane: judy watson which will be published by the Museum of Brisbane and launched on International Women’s Day 2021 (8 March).

Judy why draw attention to the women of Brisbane’s history?

Women’s stories are such an unknown, not only in Brisbane but in so many places in Australia and around the world. Women have been silenced and unrepresented in our public spaces and in our consciousness. This project is about raising the level of awareness of women and their significant contributions. It is about documenting their histories so that everyone will know the names of some of these women and understand their stories.

Can you give examples of the women whose stories you are proud to profile in the women of brisbane book?

There are more than 180 women’s stories in the women of brisbane book. There are such heroic stories of resilience and determination across Brisbane’s history. I always think about Gwai-a Catchpenny (c.1810-c.1894) who busked and danced, catching pennies in her mouth, enduring racial slurs and taunts in order to feed her family during the early years of the colony. Oodgeroo Noonuccal (1920-1993) of course was incredible. She was in the Australian Women’s Army Service (1942-44), and as a single mother worked as a domestic (including for the Cilento family) and a secretary, before she became a published author and a political activist. Alice Eather (1988-2017) conveys such power in sharing her own story (living between “this story of black and white”) as a slam poet and her work as an activist prevented the fracking of her Maningrida (NT) home. Maureen Watson (1931-2009) who I knew was an amazing writer, community elder and performer. She received the inaugural United Nations Association Global Leadership Prize for her contribution to cross-cultural understanding and harmony. I am proud to share these and so many more stories of Brisbane’s truly remarkable women.

History is defined by some as people who have made contributions to public life. What is important about the inclusion of smaller stories, of Aboriginal women and other less known figures in this book?

A lot of Aboriginal women were the silent black workforce. They came in from remote areas into Brisbane to work in domestic service, for established houses. Their stories existed below stairs – and I like the idea that these stories and their family’s stories will become part of our learned history. Even if many of the women included in the book didn’t live in the Hamilton area (where the bandarra-gan childna artwork is based), they are likely to have spent time working in the houses and walking through this area. For me you are in public life if you are out working in the community. Women also had limited access to positions of power and were overtly discriminated against in the early years of the colony and until relatively recently. Yet their contribution has always been crucial to the way society functions. In this book we have been flexible about the terms of women’s importance. A few of the women were nominated by their communities, yet detail of their story was scant (sometimes there is no detail of their story). By listing just their names we acknowledge that there is more to be told.

In this artwork and in the publication, a trail of discovery is opened to new audiences. How might the images of objects and the flora and fauna once plentiful in Brisbane, like the tow row, cabbage tree palm and the mangrove worm, change our experience of this place?

When you know the history of a place you bring your knowledge and imagination onto the site and it extends your experience. When I am at Breakfast Creek I think about the casuarinas laid down into the water to encourage an eco-system which allowed the farming of the mangrove worms. We have industrial fish farms now; this was an early and very eco-friendly way of nurturing and harvesting a great resource. After noting this imagery in the artwork you may think about Breakfast Creek differently. The cabbage tree palm is a very beautiful palm and you can eat the cabbage; it is very much a part of the diet for Aboriginal people, and the leaves themselves are so useful. They were used to make the cabbage tree palm hats and there are images of colonial men wearing them. The convict women had their heads shaved, yet they were out in the sun – making the hats was a survival practice for them. The cabbage tree is a very recognisable form, and is used in weaving everywhere. And then some people think the tow row/butterfly nets were just used in south-east Queensland, which is not true. The butterfly nets were seen in many places like Maningrida (NT), in Doomadgee up near our country. They were used all over. In the Hamilton Reach area there are a lot of historical examples and photographs noting the tow row nets and how important and beautiful they are.

Why is it important to take this information into the broader community?

I love the idea of being able to stand and sit in a place and imagine what it was like two years ago, ten years ago, one hundred years ago, a thousand years ago. Culture and memory stay within a place and if you learn about it and listen, you can feel it. That gives a richer understanding of a place and the history of people who were here and are here. We are surrounded by voices and memories and knowing allows a richer deeper connection through understanding the people who came before.

Your biography includes co-representing Australia at the Venice Biennale (1997), the Moet&Chandon Fellowship (1995), and a major exhibition at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery last year (Looking Glass, with Yhonnie Scarce, now at Tarra Warra Museum of Art in Melbourne). Early in 2021 your work is being shown at Artspace (Sydney) and in On Fire: Climate and Crisis at Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art. What does your location in Brisbane offer to your practice?

Brisbane has a troubled history and, growing up in the outskirts of Brisbane in the 1960s and early 1970s, I often felt disenfranchised from the place and the rest of community and Australia. When I left Brisbane to study in Tasmania, I was aware I carried the remnants and stereotypes of this place with me. There is a certain toughness that comes with the repercussions of those stereotypes. As a child and teenager I witnessed police brutality, the oppression of minorities and workers rights – all a part of the political conservatism of Queensland at the time. I knew that I wanted a different life and experience, not just for me but the people around me. Being back in Brisbane as an artist and Aboriginal person there is so much to work with. We have a very rich resource including the Queensland State Archives which house the categorisation and displacement of Aboriginal people and families including my grandmother and her extended family. It is something that enables me to work against the politics of the past and the present and to find my own way in this place. Brisbane is also in a unique geographical location, with so many beautiful places that I knew as a child. Brisbane is part of my own personal history and I want to use those memories in my work. I am aware of how much has changed. Reading some writers, I am aware and remember small things, banal at the time, that become significant later on. Brisbane has been a wonderful place to come back to when my children were young, and for them to go to school. I take them to places important to me, like O’Reilly’s in the hinterland, and the islands.

What narratives and opportunities continue to inspire you?

I am interested in the history of the Brisbane River, Oxley Creek, and the Indigenous history of Brisbane. A lot of industrial places were built on important Aboriginal sites, and close to where I live there are Aboriginal axe-grinding grooves I am aware of in suburban backyards. Learning more and more about that is something that I will continue to be inspired by and I try to impart that education to people all around me.

I studied English literature at the Darling Downs in the 1970s and that went onto American literature and led to knowing more about my own culture and country. The rise of my knowledge in the late 1970s and early 1980s has always led me to be interested in women and women’s stories. In my own family too I find histories that I am inspired by and continue to make work about.