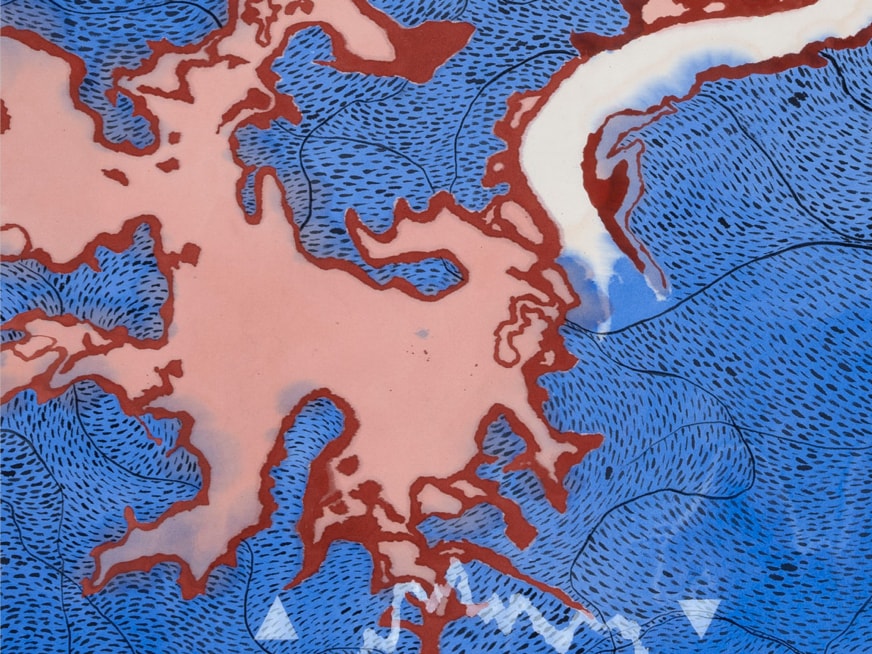

Vanghoua Anthony Vue’s site-specific installation for BrisAsia 2023, Ua li ua tau – Making do, explores themes of identity and belonging, tradition and innovation, dislocation and adaption.

We joined Vanghoua Anthony in the Museum to learn more about his residency exhibition.

MoB’s Artist in Residence Program is supported by Tim Fairfax AC.

In your practice, you often draw on your transcultural experiences as a Hmong Australian. This residency is called ‘Ua li ua tau – Making do’. Could you explain the significance of this title?

‘Ua li ua tau’ translates to ‘making do’ or more precisely, ‘do as you can’. It is a common saying that I’ve heard throughout my life from family and Hmong community members and is said when it comes to doing something that may be quite challenging. For myself, it’s an approach that I’ve taken throughout my life, especially with my art practice—both in terms of the art making and also in striving to live life as an artist.

In my art practice, I tend to move from various materials and processes based on the concept I’m exploring, including more traditional art forms such as drawing and painting to more experimental forms such as projection, installation and expanded drawing. I’m no master of any of these forms, but rather, I make do with what I know and am capable of.

Bringing it back to my family and community, the title also refers to the resourcefulness and resilience of Hmong people, in recent times and throughout history. As minorities in every nation-state, the Hmong people have consistently been pushed to the margins of society, having to make do with what is available on the margins and having had to make homes and live across mountaintops that others may consider uninhabitable. Additionally, and despite having to forcefully leave previous homes in South East Asia, Hmong Australians have also made do and created homes here in Australia.

There are layers upon layers of meaning in your work, and certain elements find inspiration in the imagery of Hmong textiles – what is your connection to this tradition, and how have you sought to reinterpret it in an Australian context?

My connection to Hmong textiles is actually more about my disconnection to this tradition and more broadly my Hmong cultural heritage. In fact, a lot of my work draws more from my personal experiences, and as a result, my Australian cultural heritage. It always seems to be that viewers see the Hmong aspect of my work more so than the Australian aspects. But in many ways, I’ve been trying to reconnect and explore Hmong cultural traditions, especially visual art traditions, through what I know.

For the work in this exhibition, I use a wide range of materials and processes that are not used in Hmong textiles—again, using what I know—wooden panels, everyday items, DIY processes, and invented symbols and designs.

Another reason I use non-textile materials and processes is also as a reflection on how detached Hmong textiles have become from cultural practices and historical significance. Most of this is due to heavy commercialisation and exploitation, where these fabrics and patterns have been bastardised across different parts of the world—by Hmong and non-Hmong alike—placed on products from bedsheets to cups to high fashion. Largely for aesthetic purposes and ethnic appeal. There’s a lot of desire for ‘the different’ under the umbrella of appreciation, but only in terms of what is palatable and consumable.

Additionally, Hmong traditions, including clothing and everyday objects, have been placed in museums and displayed as relics and static objects of the past even though they continue to be used by members of the Hmong community. I’m reverting that idea with the objects and materials I use, bringing everyday items such as cooking utensils and sporting equipment into that context to question the museum and its role in categorising and defining objects, peoples and their cultures.

Your residency features interviews with members of the Hmong community, installed above a dreamlike montage of refugee camps you visited while in Thailand. What is the relationship between these two videos, and what was your experience making them?

Yes, one video is of local Hmong community members in Cairns and Logan who discuss their experiences of their time in refugee camps in Thailand from the mid-1970s to the late 2000s. It was a very rewarding experience to record their stories—which was something I’ve been meaning to do for a very long time now. I am really appreciative of those who were willing to share their experiences, especially as some of their experiences were unpleasant and difficult to talk about.

The other video shows overlapping recordings I made of nine sites I visited across Thailand in 2020. These sites are former official and unofficial refugee and transition camps in Thailand, as well as several key crossing points along the Mekong River between Thailand and Laos that many Hmong asylum seekers crossed. Being able to visit these sites and make these recordings was really challenging, especially because it was during the peak of COVID-19 in 2020. Long solitary hours were spent driving to and from these sites, and there were many days of quiet contemplation.

Significantly, it was about finally setting foot in these places that I had heard so much about—despite the fact that they had significantly changed and that history had moved on. For my parents and other members of the community, these places are still fondly remembered, even though they were very long, drawn out periods and places of trauma and uncertainty.

Creating these videos is a way for me to remember my own journey to these sites, but also a way to honour those in the video and their continued acts of remembering, which no one else has really cared for but them.

Water features throughout your work, with three videos focusing on the Logan River, the Mekong River and the Brisbane River. What is your relationship to these bodies of water?

It’s a funny relationship I have with water, I have a deep fear of it actually, especially large bodies of water. I can’t swim and I’ve nearly drowned multiple times in my life. It is, however, a significant part of my past and my present.

The Mekong River (the central video) is significant because of recent Hmong history—especially through the stories my father has told me of his escape to Thailand. Many of the experiences discussed by those in the video are also of crossing the Mekong River. The video included in the exhibition of the Mekong River is actually where my father crossed over on a makeshift floatation device made from bamboo sticks. It was taken from Pak Chom in Thailand and looking across over to Laos on an early morning. Laid over this video is also a recording of a poetic Hmong mouth harp song played by a Hmong elder about his experiences of immigration and loss.

To the right of this is a video of the Brisbane River. Specifically, it is at West End and looking over to Saint Lucia. When I first moved to Brisbane after high school I lived in that area and regularly took the ferry from Guyatt Park to get to the Queensland College of Art at South Bank. Then on the left is a recording of the Logan River—close to where I currently live and often drive past. Logan is also where many of the Hmong community members live in the Brisbane region.

In the exhibition, these videos have been arranged and composed together to connect the flow of water from these three rivers and tie my personal story and history to those of my family members and the Hmong community in the Brisbane region.

Over the course of the residency, you will be adding to your installation using found and locally sourced materials. What is your process in creating these sculptures?

Even though I start off with a plan for these sculptures, it is all very intuitive and the plan does go out the door. Sometimes very early on in the making, and at other times midway through. But the work never turns out as I initially envisioned. Much of the work is about looking and projecting—or imagining how it would look with certain aspects added, subtracted, adjusted or rearranged—and much of that is dictated by the materials on hand. Each element added is the basis for the next, and that’s the same for my sculptures as well as other strands of my practice.

However, a significant part of making these sculptures is the selection of materials, which happens away from the studio space and instead at discount stores, homes and recycling centres.

For these sculptures, I’ve been sourcing and using things found at home, particularly those everyday and underappreciated tools and objects we use to create and ‘make do’ at home. Most of these items are also selected based on how well their colours, materials and forms resonate with other elements of the exhibition. That’s the most challenging part of the process, and then the rest is just serious play and obsession.

Explore Vanghoua Anthony Vue’s residency exhibition at Museum of Brisbane.